In 2023, KB, National Library of the Netherlands will launch a new Special Collection ‘Museums on the Web’. This collection of Dutch museum websites unlocks an essential (and the largest) sub-collection within the KB web archive, which offers the potential to research histories of museums on the Web within the Netherlands. In this first blog, we will highlight some significant case studies within this history.

Twenty-five years ago, the first European museum websites appeared on the World Wide Web, today the digital space and online activities have become an integral part of every museum’s vision and practice.¹ The advent of online technologies has changed the way museums manage collections and access them, shape exhibitions, and build communities and participation. Finding effective forms of digital engagement became especially urgent during the mass closure of the museum buildings during the Covid-19 pandemic. And museums continue to face new challenges in today’s fast-changing digital landscape, like the rise of AI and the semantic Web. But how did we come to this point, what are the museums’ online legacies? By engaging with the past, we can enhance our understanding of how museums are functioning on the Web today and offer new perspectives for future developments.

The KB web archive holds important primary sources that can unlock these histories. The special web collection ‘Museums on the Web’ offers access to these sources through a selection of curated archived websites from The Netherlands, and it will be the first KB special web collection that is accessible through a SOLR Wayback search engine, which makes it possible to request datasets and explore the collection through a series of dashboards. This offers the opportunity to study histories of museums on the Web in The Netherlands, combining methods from history and data science and drawing on a computational analysis of Web archive data.

In order to showcase the diversity of museum websites, this first blog will highlight some significant case studies.

The Temporary Museum (1989, 1993)

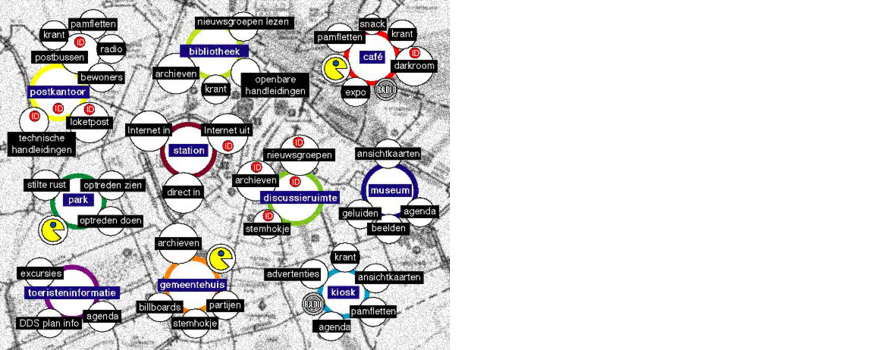

Figure 1. Walter van der Cruijsen, Map of the Digital City (de Digitale Stad), Hypercard, Illustrator, Photoshop, 1993.²

The emergence of the World Wide Web caused a powerful impetus to the development of virtual museums, in particular the introduction of the Mosaic browser in 1993 that allowed to enter a multimedia environment online.³ In these early days of the Web, the ‘Temporary Museum’ opened its doors on the homepage of the Digital City (DDS).⁴ The Digital City was the first virtual city in the world. By then, there was only a small group of Internet users in the Netherlands and the DDS aimed for lowering the barrier to enter the Web through a user-friendly interface and public terminals that were spread around the city of Amsterdam. The website represented a city, one could occupy a home and discuss ideas on the forum, and in the first graphical interface the ‘Temporary Museum’ was located on the city’s square.⁵

The idea for the ‘Temporary Museum’ developed in 1989. Artist and DDS co-founder Walter van der Cruijsen envisioned a museum for housing dynamic, floating artistic ideas; the virtual realm seemed the archetypical space to frame these artworks. In response to the discourses around virtual reality, the ‘Temporary Museum’ represented a ‘knowledge space’ where the mind could wander around, explore ideas and form new ones.

The museum’s mission was to continuously collect new ideas and store them in the ‘Temporary Warehouse’. After filling the container, the museum would transition into the “Museum of Infinity”. Each full container was copied and distributed, artworks would manifest themselves in endless streams and that to preserve them for future generations. Already within this pioneering concept we can discover a radical shift in museum culture. Instead of focussing on the unrepeatable and unique, the virtual museum housed artworks that were in a constant state of flux to stay ‘alive’.

Rijksstudio (2012-now)

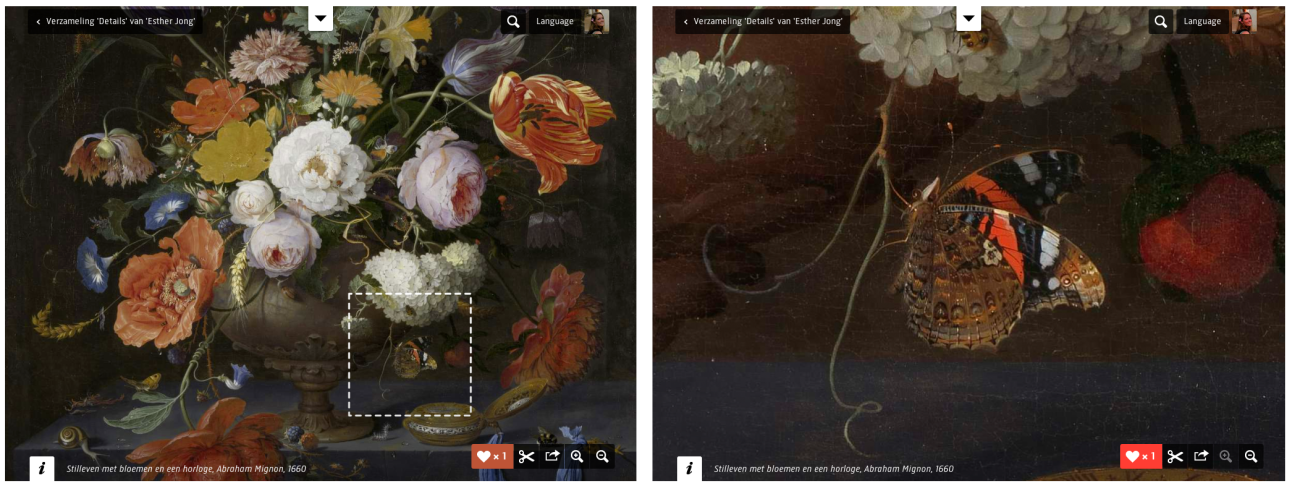

Figure 2. Fabrique, Rijksstudio, 2012-now, www.rijksmuseum.nl/nl/rijksstudio.

A museum that was regularly at the forefront of web development within The Netherlands (and abroad) is the Rijksmuseum.⁶ One highlight was the development of the Rijksstudio that was released in 2012 to make their collection online available and increase visitor’s engagement.⁷ Today, the Rijksstudio contains more than half a million artworks. High quality photos of the artworks can be viewed full screen, it is possible to zoom into details and both the artworks and selected details can be saved in personal collections. The museum released the images under a public domain license and encourages creative (re)creations, such as generating material for upholstering furniture, translating it to printable knitting patterns, or creating 3D objects with a laser cutter or 3D printer.⁸

The majority of the Rijksmuseum collection items are now part of the public domain, and the museum continues to develop a culture of open data publication. Not only the images, but also metadata and descriptions of collection items are openly available on the World Wide Web. The Rijksmuseum was one of the first museums in the Netherlands providing access to their datasets using Linked Data.⁹ While many applications are still in development, it offers the potential to achieve cross-referencing and integration with other data sources, like other museum collections, libraries or sources on the live Web (e.g. Wikipedia). Linked Open Data could contribute significantly to adding new perspectives, enriching artworks with new (and dynamic) meanings and values, but also making knowledge processes more efficient within cultural heritage organisations.

Jan Bot (2018-now)

Video 1. Pablo Núñez and Bram Loogman, Jan Bot commissioned by EYE Filmmuseum, 2018-2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tGLqVytlvKI&ab_channel=JanBot.

Although that the virtual is in itself invisible, its influence on the museum as a memory institution is far-reaching. Virtual collections are continuously growing, reaching an unimaginable size and humans alone are no longer able to process them. We are at the forefront of exploring new collaborations between man and machine, in which artificial intelligence may increasingly support curators to find new areas for discovery.

A demonstration of an artificial intelligence tasked to explore a museum collection is ‘Jan Bot’.¹⁰ Initiated in 2018, this robot was developed to further explore the ‘bits and pieces’ collections at the Eye Museum, the film museum in Amsterdam. Film archives regularly receive short excerpts of films of which it is very complex to identify them, yet it can still be valuable to preserve them. These short fragments, often incomplete, form the ‘bits and pieces’ collection. Jan Bot was tasked to explore this collection. It matches trending topics on social media with early twentieth century footage to generate short, experimental films.¹¹ Through creating a huge amount of original work, Jan Bot also contributes to larger debates about the aesthetic potential of artificial intelligence. Is it possible to expand the horizons of human artistic expressions?

Today, it is still possible to visit the website ‘www.jan.bot’. With an average of 10 films per day, by now Jan Bot generated more than 25.000 films and there are continuously new films added to his archive. Producers Pablo Núñez and Bram Loogman did announce that it is time to start planning a funeral event and envisage his afterlife.¹² Now that NFT artworks are vastly developing, it seems fitting to preserve his filmography in the blockchain.

Throughout time, there are continuously fierce discussions if we should prioritize exploring state of the art technology or actually humanizing processes. Yet the experiments that may be most interesting are those that leave this dichotomy behind and further explore how technology is able to extend human capacity or where technology becomes humanized. It is no surprise then, that within this development also the virtual museum could finally reach its post-digital stage, becoming a hybrid form, in which the online and offline realm are fully integrated [Parry 2013]. Most likely, the virtual museum as a self-contained institution will disappear (and this may already be the case), as it will become increasingly complicated to separate it from the physical museum itself.

[1] Ross Parry, “The End of the Beginning: Normativity in the Postdigital Museum,” Advances in Research - Museum 1, no. 1 (July 1, 2013): 24–39, https://doi.org/10.3167/armw.2013.010103.

[2] Theus van den Doel, Gevonden: Ontwerp van stadsplattegrond DDS: Ontwerp van Walter van Cruijsen uit 1993, 2015. 19 December 2020. [https://hart.amsterdam/nl/page/53050]. Internet archive. [https://web.archive.org/web/20200919184230/https://hart.amsterdam/nl/pa…].

[3] Giuliano Gaia et al., “Museum Websites of the First Wave: The Rise of the Virtual Museum,” in Proceedings of EVA 2020, London (UK), https://doi.org/10.14236/ewic/EVA2020.4.

[4] Walter van der Cruijsen, The Digital City, 1994. 24 July 2002. [http://www.desk.org:8080/Desk/The+Digital+City]. Internet archive. [http://web.archive.org/web/20030129090055/http://www.desk.org:8080/Desk…].

[5] Walter van der Cruijsen, het Tijdelijke Museum, 1994. 3 September 1999. [http://www.thing.desk.nl/wvdc/dds1/A/TM.html]. Internet archive. [https://web.archive.org/web/19990903201854/http:/www.thing.desk.nl/wvdc…]

[6] Their website won many awards, including the most recent revamp (2020) was awarded the GLAMi2021 for the innovative design and the new Stories platform.

[7] Fabrique, Rijksstudio, 2012. 7 February 2023. [www.rijksmuseum.nl/nl/rijksstudio], KB Web archive [http://webaccess.kb.nl:8080/archived/20130207161958/https://www.rijksmu…]. Please note that the KB Web archive is only accessible within the KB reading rooms.

The Rijksstudio was the winner of the ‘Best of the Web’ award under the category “innovative / experimental” at the Museums and the Web conference 2013. https://mw2013.museumsandtheweb.com/best-of-the-web-winners/index.html

[8] Peter Gorgels, “Rijksstudio: Make Your Own Masterpiece!” in Proceedings of Museums and the Web 2013, Portland (USA), https://mw2013.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/rijksstudio-make-your-own-mas….

[9] Chris Dijkshoorn, et al., “The Rijksmuseum Collection as Linked Data,” Semantic Web 9, no. 2 (January 1, 2018): 221–30, https://doi.org/10.3233/SW-170257.

[10] Pablo Núñez and Bram Loogman, Jan Bot, 2018-2022. 16 June 2018. [www.jan.bot]. Internet archive. [https://web.archive.org/web/20180713173848/https://www.jan.bot/].

[11] Jan Bot, MIT – Docubase. October 26, 2020. [https://docubase.mit.edu/project/jan-bot/]. Internet archive. [https://web.archive.org/web/20201026072515/https://docubase.mit.edu/pro…].

[12] Dan Schindel and Ben R. Nicholson, “An Experimental AI Film Director Calls It Quits,” Hyperallergic, 31 July 2022, http://hyperallergic.com/750870/jan-bot-amsterdam-filmmuseum-filmmaker-….