From February to October 2024, I had the privilege of working as a researcher-in-residence at the National Library of the Netherlands. The aim of my residency was to prepare the early modern theatre editions available in the DBNL for computational studies of early modern Dutch drama. In this blogpost I present the first result of that effort: a corpus of 180 early modern Dutch plays, fully encoded and annotated in TEI XML according to the standards prescribed by the international theatre database developed by the Drama Corpora Project (DraCor).

In the last three decades, the access to digital theatre corpora has increased dramatically. Because institutions such as the Folger Shakespeare Library, the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) and the National Library of the Netherlands (KB) were quick to digitise their theatre collections, digital reproductions of early modern theatre editions have been available on the web for many years. The online access to these editions has opened up Western theatrical heritage to students, scholars and other readers. For the Dutch context, the main collections of digital theatre editions can be found in the Digital Library for Dutch Literature (DBNL, maintained by the National Library of the Netherlands) and the Census Nederlands Toneel (Ceneton, which was developed and edited by Ton Harmsen at Leiden University). Thousands of students have first discovered the richness of plays by Joost van den Vondel, G.A. Bredero or Catharina Verwers through those collections.

Recently, theatre scholars recognised the additional potential of the existing repositories for comparative research into historical theatre traditions. They applied methods and concepts from other fields, such as network theory (e.g. Moretti 2011), economics (Algee-Hewitt 2017) and the history of emotions (Leemans et al. 2017), to model features of the text and structure of those plays, such as character interactions, social composition of story worlds, or emotional expressions. Those abstractions enabled researchers to systematically compare hundreds or even thousands of plays. Including this larger scale of analysis in historical drama research is necessary to identify and describe patterns and developments across time periods and even (language) borders. A great introduction into the state of the art of this young research tradition can be found in the recently published collection Computational Drama Analysis (2024) edited by Melanie Adresen and Nils Reiter. For the Dutch context, my recent article on theatre society Nil Volentibus Arduum offers a good impression (Van der Deijl 2024).

The Drama Corpora Project

Computational approaches to historical drama benefited significantly from the initiative by Frank Fischer, Peer Trilcke and everyone else from the Drama Corpora Project (DraCor) to create a so-called ‘programmable corpus’ of theatre editions from multiple European languages (Fischer et al. 2019). All editions included in the DraCor-database are fully encoded in TEI XML, which means that all structural elements in the play are labelled separately: acts, scenes, speech turns, speaker indications, stage directions et cetera. Moreover, the text from the editions is manually annotated with additional metadata. All speech turns are disambiguated with unique character IDs and all characters received a gender label. This step enables the extraction of speech turns by character or by gender group, for example. By introducing a cross-lingual standard for the encoding and annotation of theatre editions, DraCor facilitates and standardises computational analyses of dramatic texts from various linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Moreover, through its interoperable API (Application Programming Interface; an entry point for computers), the database can be questioned and queried on various levels using programming languages.

However, until recently there was no Dutch corpus available in the DraCor infrastructure. Due to this omission, Dutch-language theatre traditions have been a blind spot in current debates on computational drama research (with a few exceptions: Leemans et al. 2017; Debaene et al. 2024). The rich theatre culture from the Dutch language field thus tends to be overlooked, even though the DBNL and Ceneton already contain hundreds of high quality transcriptions of early modern theatre editions. Converting those editions to DraCor’s encoding standard would connect Dutch drama to other European theatre traditions, which have always been key to its development. As a response to this lack of a suitable Dutch theatre corpus, I collaborated with experts from the KB and with students from the University of Groningen to develop a first selection of 180 fully encoded Dutch plays. This corpus has been integrated in the DraCor infrastructure and will continue to grow in the future under the name of the Dutch Drama Corpus (DutchDraCor). In this blogpost, I briefly describe the characteristics of this corpus at the moment of its second release in October 2024.

DutchDraCor: characteristics and statistics

In October 2024, DutchDraCor contains 180 fully encoded plays, with 2.117 speaking characters or character groups (including 1.364 male character (groups) versus 514 female character (groups)). The corpus includes over 2.3M words, 60.021 speech turns and 5.750 stage directions. 151 editions were derived from DBNL and 29 plays (the complete oeuvre of theatre society Nil Volentibus Arduum) were collected from Ceneton. There are 68 distinct first authors or author groups represented in the corpus, excluding translators. Some authors or groups are overrepresented in the corpus due to their large production and overrepresentation in the source collections, such as chamber of rhetoric De Pellicaen (39 plays), Joost van den Vondel (31), Nil Volentibus Arduum (29), and Jan Harmensz Krul (9). The corpus contains both plays originally written in Dutch and Dutch translations of plays written in other languages – mostly French, Latin and Spanish – as translations and adaptations were an important part of the early modern literary production in the Low Countries.

Coverage and representativeness

Assessing the coverage of DutchDraCor is not straightforward, as it is not evident how to measure representativeness. In an ideal world, the corpus should contain a representative sample of all plays that were written, printed and staged in Dutch between 1500 and 1800. Since there are no reliable estimations of all plays that were once written and or performed in the early modern Low Countries, I cannot quantify the relationship between sample and ‘population’. Instead, I will point to a few important biases in the corpus in terms of year of publication, genre and author gender.

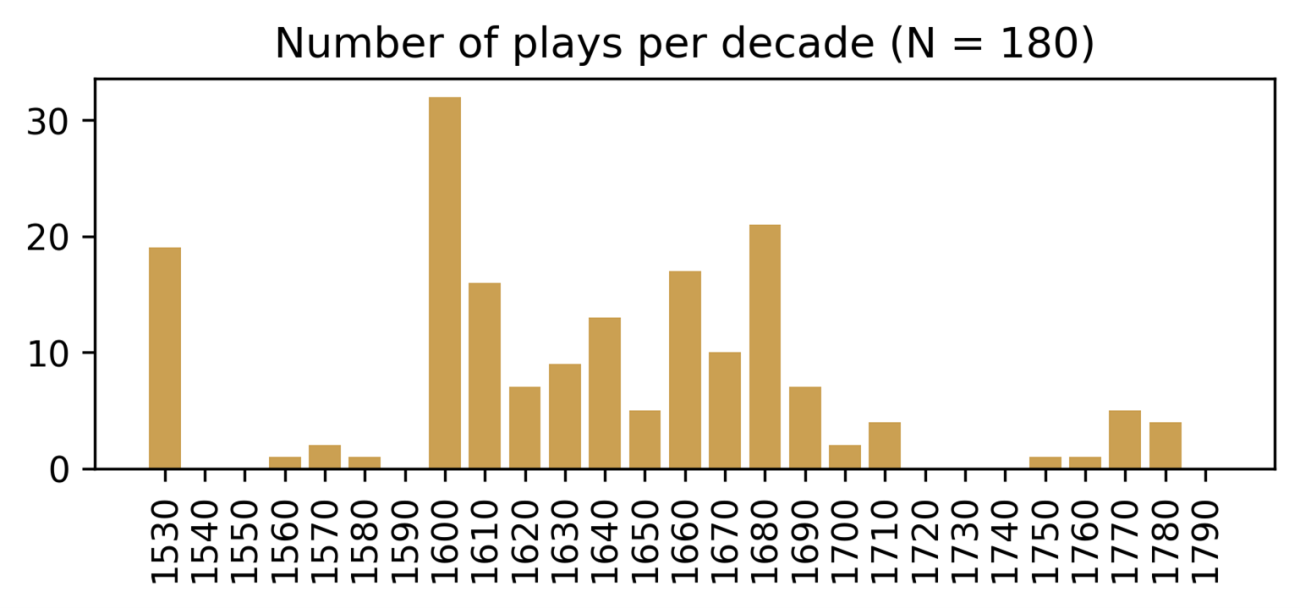

First of all, plays from the sixteenth and eighteenth century are underrepresented. The bar chart below shows the number of plays written or printed per decade, confirming that DutchDraCor is especially useful for studies of seventeenth-century drama. Future additions to DutchDraCor will need to correct for this temporal imbalance.

Secondly, the corpus is not balanced in terms of genre. The most frequent genre labels are tragedy (‘treurspel’), morality play (‘zinnespel’) followed by comedy (‘blijspel’) and farce (‘klucht’). There is also a temporal imbalance in this genre distribution, since most morality plays were written in the sixteenth century, whereas most tragedies were written and printed in the seventeenth and eighteenth century.

Finally, there is no equal gender balance among the authors represented in the corpus. The vast majority of the authors in the corpus is male: only 18 plays (10%) were written by women: 7 by Katharyne Lescailje, 7 by Lucretia Wilhelmina van Merken, 3 by Catharina Questiers and 1 by Catharina Verwers. Like the biases concerning period and genre, this overrepresentation of male poets is partly caused by the imbalances in the used collections (DBNL and Ceneton) and in the extant source material digitised in those collections. Computational approaches of early modern Dutch drama based on DutchDraCor need to take these biases into account, including the stage in the history of the editions where the bias was introduced (from writing, to printing, collecting, archiving, digitisation and encoding).

Where to find DutchDraCor

The full corpus is available through the DraCor infrastructure, which offers various downloadable representations of the plays and the metadata about the plays. The corpus can also be downloaded in full via GitHub. DutchDraCor will continue to grow in the future, but a standalone version of the corpus described here will become available via Zenodo. Enjoy!

In my next blog post, I will demonstrate the value of DutchDraCor by taking the gender balance in the corpus as a case study rather than a bias, questioning the position and visibility of female characters on the stages in the Low Countries.

Acknowledgments

DutchDraCor was created with the assistance of many contributors: Teun de Vries, Hinke van Minnen, Mirthe Wubs, Mirte Triezenberg, Jasmijn van Valkenburg, Hilde Bos, Marc Bos, Melissa Nijboer, Thirza Fokkens, Jarick van der Wal, Anna Lap, Maurice Eeftink, Annechien Hussem, Jens Klein, Jan de Vries, Hidde van Deemter, Ivar Czudar, Evi Dijcks, Alie Lassche. Special thanks to Willem Jan Faber, Suzan Boreel and everyone from the digital scholarship team at the KB.

For the creation of DutchDraCor Lucas van der Deijl was supported by the National Library of the Netherlands (KB) during a residency from February to October 2024 and by CLS INFRA during a Transnational Access (TNA) fellowship at the University of Potsdam in April 2024.

References

Adresen, Melanie and Nils Reiter. Computational Drama Analysis: Reflecting on Methods and Interpretations. Berlin, Boston 2024.

Algee-Hewitt, M. ‘Distributed Character: Quantitative Models of the English Stage, 1550–1900’. New Literary History 48 (2017) 4, 751-782.

Debaene, Florian, et al. ‘Early Modern Dutch Comedies and Farces in the Spotlight : Introducing EmDComF and Its Emotion Framework.’ Proceedings of the Third Workshop on Language Technologies for Historical and Ancient Languages (LT4HALA) @ LREC-COLING-2024, edited by Rachele Sprugnoli and Marco Passarotti, ELRA and ICCL, 2024, 144–55.

Deijl, L.A. van der. ‘Orde en rationalisme in het toneel van Nil Volentibus Arduum. Een computationele benadering van vroegmoderne verhaalmodellen’. Spiegel der Letteren 66 (2024) 1, 53-94.

Fischer, Frank, et al. ‘Programmable Corpora: Introducing DraCor, an Infrastructure for the Research on European Drama’. In Proceedings of DH2019: "Complexities", Utrecht University, 2019.

Leemans, Inger, et al. ‘Mining Embodied Emotions: A Comparative Analysis of Sentiment and Emotion in Dutch Texts, 1600-1800’. Digital Humanities Quarterly 11 (2017) 4.

Moretti, Franco, ‘Network Theory, Plot Analysis’, Stanford Literary Lab Pamphlets 2 (2011).