As a geographer working at the KB thanks to the researcher-in-residence program, I am currently investigating how the image of Dutch cities changed in newspapers since the second half of the XIXth century. Throughout this research, I am working together with Willem Jan Faber, who is implementing all the different steps related to the data collection.

The geographical nature of news

One of the main outcomes of the digital turn in the humanities is the possibility to identify long term macroscopic trends that were not possible to grasp with qualitative approaches. Over the last couple of years, the use of quantitative methods to study digital collections of newspapers has led to successful applications notably in cultural and historical research. But despite the ‘inherent geographical nature of news’[1] only a few studies have looked at the spatial dimension of these type of sources.

Obtaining data that gives information on cities over long periods of time is very important to understand their dynamics. But such data is not so easy to obtain because of the chequered history of census and the challenge of harmonizing their categories that are changing through history. However, newspapers are a very rich source of information on cities. As Armand Frémont said, ‘what it is written in the press about a city allows to know the major themes of the urban life and physiognomy urged upon the readership’[2]. This type of source is especially interesting because newspapers used to be the backbone of information diffusion before the rise of electronic and digital media and many researchers have highlighted the central role of information in urbanization process[3].

Figure 1 – Advertisment for the Leidsch Dagblad in the Provinciale Geldersche en Nijmeegsche courant on 11-03-1927

“By advertising in the LEIDSCH DAGBLAD you can reach Leiden and all surrounding places such as Katwijk, Noordwljk, Vooreohoten, Wassenaar, Zoeterwoude, Sassenhelm, Oegstgeest, Rijnsburg, etc. etc., and the whole Rijnstreek, the largest number of families of all classes.”

https://www.delpher.nl/nl/kranten/view?coll=ddd&identifier=MMRANM02:000…

The aim of my research project is to reconstruct the mental map of newspapers’ readership at different periods in order to understand how the different cities of the Dutch urban system where perceived. My research involve 3 main steps: selecting a corpus, filtering the articles with city names, and analysing the content of these articles. In this blog post, I will report about the second step that is filtering the articles mentioning cities.

The ambiguity of place names

City names, and place names in general are subject to many ambiguities. For example a single place name can have multiple meanings such as “Leiden”, which refers to a city in South-Holland but also means ‘to lead’ in Dutch. Another problem is that in many cultures place names are regular features of family names (François Hollande and Royston Drenthe being notorious examples). In a recent research that we did with a colleague[4], we found out that about 14% of the names of settlements of more than 750 inhabitants (villages, towns and cities) in the Netherlands have an ambiguous name that could lead to false positive or true negatives when retrieving them with simple string queries.

Having each article checked by humans is of course the best solution because we can solve these ambiguities by taking into account the context in which the place is mentioned. This is how quantitative researchers working on newspapers used to do in the past. For his very interesting study on the spatial determinants of information circulation published in 1946[5], G.K. Zipf had to employ 18 students[6] from his class of social psychology at Harvard University to count the number of times cities were mentioned in the obituaries of The New York Times for a three years period, and in the news-items from the five firsts pages of each edition of The Chicago Tribune also for three years. Today, thanks to significant efforts to digitize historical newspapers, coupled with the development of computational techniques, it is now possible to investigate this kind of data systematically with a limited cost of data collection, but this implies a careful choice of the method.

The “Best” problem

The two main options for our data collection were to use basic string queries or Named Entity Recognition (NER). The first one implies to match our list of cities with the content of the news-items and keep only the ones that received a positive answer. The second one is a technique used in Natural Language Processing that allows to locate and categorize pieces of text into categories (locations, persons, organisations, monetary values, etc.). We compared the number of occurrences of several places, ambiguous or not in 24 different newspapers on a period of 130 years. We plotted the result for two cities: Dordrecht, a city of South-Holland, which have very low chances of having false positives, and Best, a town close to Eindhoven which is also a very common word in Dutch (Figure 1). This figure shows the risk of overestimation with places like Best.

Figure 2 – Comparison of two toponyms recognition techniques for Best and Dordrecht

A trade-off between refinement of the method and computing time

While NER is a much more advanced and precise technique, it has the main drawback of being slower than string matching. The software engineers of the KB have developed a very accurate NER/ disambiguation algorithm that compares the outcome of three different NER-algorithms and looks at the different named entities found in the articles and their context (as well as within the corpera as in wikidata/dbpedia) to solve ambiguity problems. However, this algorithm takes several seconds to process an article, which can turn rapidly into months for a corpus as big as the one we are working on. String queries present the main advantage of being very fast but comes with over- and underestimations. In order to reduce the number of errors without increasing the computing time needed too much, we decided to go for a mixed technique that simply look for strings corresponding to our list of city names, except for 24 cities (such as Leiden, Assen, Hoorn, Best, etc.) for which we are using NER.

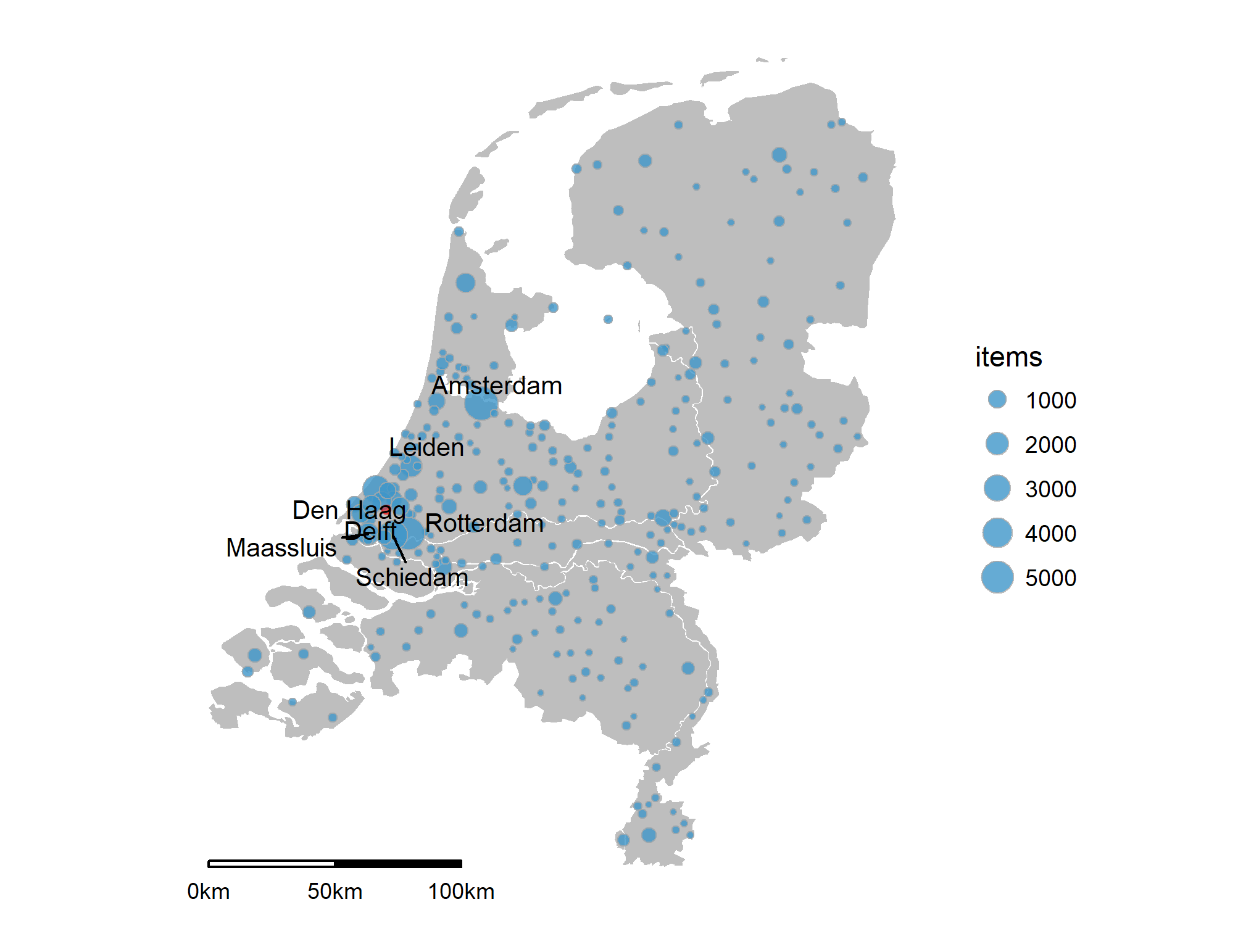

Now this data has been collected (see Figure 2 for preliminary results) we are now investigating the content of these ‘urban news’.

Figure 3 – Cities and towns mentioned in the Delftsche Courant between 1870 and 1880

[1] Susan R. Brooker-Gross, "Spatial Aspects of Newsworthiness", Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human Geography 65, no 1 (1983): 1‑9, https://doi.org/10.2307/490840.

[2] Armand Frémont, La région, espace vécu (Presses universitaires de France, 1976).

[3] Anne Bretagnolle and Alain Franc, « Emergence of an integrated city-system in France (XVIIth–XIXth centuries): Evidence from toolset in graph theory », Historical Methods: A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History 50, no 1 (2017): 49‑65, https://doi.org/10.1080/01615440.2016.1237915.

[4] Evert Meijers and Antoine Peris, “Using toponym co-occurrences to measure intercity relationships: review, application and evaluation” (forthcoming)

[5] George Kingsley Zipf, « Some Determinants of the Circulation of Information », The American Journal of Psychology 59, no 3 (1946): 401‑21, https://doi.org/10.2307/1417611.

[6] They are all listed in the footnotes of the paper.